Image header: Drmirshak, CC-BY-SA-4.0

If you’re tuning in just now, please read Part 1 to get the context.

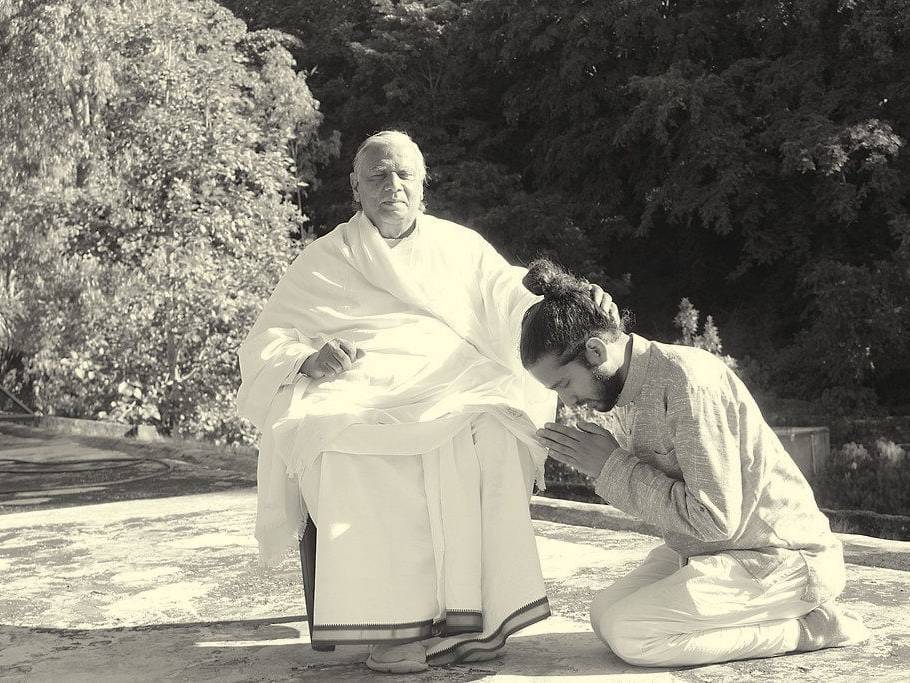

In little more than 100 years since its cultivation in the West, yoga has significantly changed its face from its ancient origins, which date back 5,000 or more years. The exact beginnings cannot be determined, as the origin of the Vedas remains untraceable despite years of research. The Vedas are considered the oldest literary document of Indo-Aryan civilization and the most sacred scriptures of Hinduism. They contain the accumulated spiritual knowledge on all aspects of life that has been passed down orally from guru (teacher) to chela (disciple), unadulterated from generation to generation in the parampara system since time immemorial. Parampara is Sanskrit and means an unbroken line or series, order, succession, continuation, transmission, tradition. In the seclusion and tranquility of the forests, teachers gathered their students in so-called ashrams. In these early times, yoga was a spiritual practice. It was devoted to contemplation and meditation with the sole aim of self-realization, enlightenment and moksha, the complete liberation from the cycle of birth and death, i.e. transcending the limitations of worldly existence while attaining full awareness of ultimate reality. The Sanskrit term yoga has the meaning of “to join, to unite.” Literally, it means “yoke” in English, “jogue” in French, or “yugo” in Spanish. Since Sanskrit is related to Greek and Latin, and thus to all other Roman languages, the similarity of the word roots is not surprising.

With the teachings written down, the high goal of yoga, the close relationship between guru and disciple, was maintained. As the teachings were recorded in a secret, coded form, they were accessible only through initiation of the student by his teacher. This era produced a wealth of classical literature on yoga: the Upanishads, the Yoga Vasistha, the Bhagavad-Gita. The latter, written in 500 B.C., is one of the most important scriptures of Hinduism and yoga. Although embedded in the larger work of the Mahabarata epic, the Bhagavad-Gita, or Gita in short, is a self-contained Upanishad. Highly praised by Mahatma Gandhi, as well as Aldous Huxley, Ralph Waldo Emerson, C.G. Jung, and Hermann Hesse, it can be considered the most concise manual on Hindu theology, as well as a practical guide to life.

Along with the Bhagadvagita, the Yoga Sutras on the Raja (‘royal’) practice of yoga, which are taken up sooner or later by seriously ambitious students of yoga, are considered the most important scripture on the science of yoga. Patanjali, who probably wrote them in the 2nd century AD, is often mistakenly thought to be the ‘father of yoga’. However, it was not until several centuries after Patanjali that the body was included in the practice. It came to be seen as a temple that housed the immortal soul, whereas previously the body had been seen merely as a container. The spiritual teachers’ growing concern for society, as well as the discovery of techniques to energize the body, led to a more socially acceptable, physical form of yoga called hatha yoga. These were the raw beginnings of physical yoga as we know it today.

Image: Yogainrishikesh, CC-BY-SA-4.0

Dr. Georg Feuerstein, an Indologist specializing in yoga, explains the following, “While there has been a great interest in the discipline of yoga, we don’t yet have the proper context for an authentic engagement of yoga in the West. And that is why it’s not working.”

Yoga was not designed as a series of exercises to achieve a nice bum, nor as a fitness program. The goal of yoga, he said, is ultimately spiritual liberation.

“Its philosophy is not rooted in a physical culture of health and wellbeing alone, as is most emphasized today… but instead it springs forth from an entire approach to existence, which was based upon higher values… …values upon which the entire fabric of the Vedic culture of ancient India itself was constructed.”

The fact that some Indian yogis were so advanced that they sent their disciples to the West to become what they became suggests that these yogis saw both a need and a certain readiness, a maturity, for uprooting and transplanting the yoga tradition, so to speak. They must have anticipated the adjustments that yoga would have to make to adapt to Western soil. At the same time, they must have valued the benefits of yoga to Western society more highly than the “damage” the adjustments would do to the yogic tradition. After all, it was their compassion that made the leap possible.

Image: Soham.yoga, CC-BY-SA-4.0

Critics counter that yoga has been watered down and cut off from its highest spiritual essence. And perhaps they are right.

However, the number of people practicing yoga outside its homeland shows that there is obviously a great demand.

It indicates that – even if, or precisely because, religion in our Western world is like a patient who seems to be slowly sliding into a coma – there is definitely a need for something profound.

In a world in turmoil, rocked by financial, political and social crises, dominated by consumerism, constricted by fear, social conditioning and high expectations, with no firm connection to higher values and ideals, the need for rootedness, meaningfulness and expansion of our being is undeniably present.

What we need, however, should not be stale, aloof and out of touch with reality, but contemporary and applicable, which takes into account our busy, complex lives, is flexible enough to meet our diverse individual needs and offers simple tools. We may not want to call it that, but in the end it is nothing other than a longing coming from our spiritual side.

Weeks later, I was walking through town with a friend and stumbled across posters of the yoga school with the 3 H slogan. I pointed them out to him.

Hot, hip and holy, my friend muttered. That’s so tacky, he said.

He was a Buddhist, the kind you don’t wonder if they are. The kind who wore ochre or terra cotta colored, flared pants, arm warmers and lots of colorful cotton scarves, unflattering glasses and a funny hairstyle, if you can even talk about it.

Don’t you think it’s clever, I asked him.

Oh come on, he said, it’s fishy to mention “Holy” in the same breath as “Hip and Hot.”

That’s exactly the point, I remarked.

He turned up his nose and pulled a face in disgust.

He didn’t see what I saw.

You may also like

So simple we might forget about it – the hidden power of breathwork

Focusing on our breath, It's a powerful practice that…

How we get hooked on negative emotions

Just like how people can get addicted to drugs, we can get…

Somebody Somewhere Some Time – If we feel lonely

“I sometimes walk around the neighborhood at night, just…