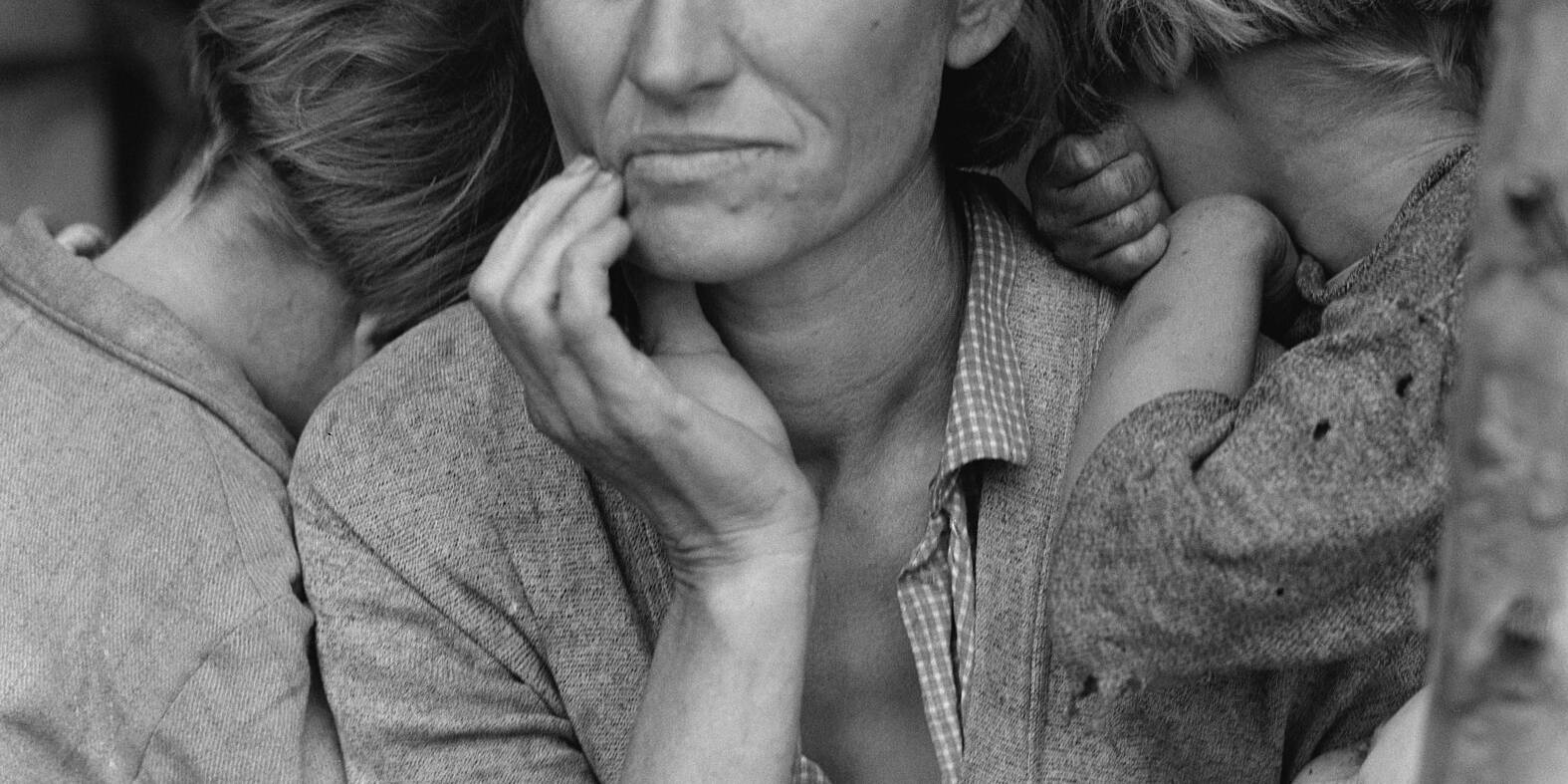

Image header: Angela Sevin, CC BY-NC 2.0

It was a hot summer day when I decided to get on my bike and ride out of town. I went to the river where you could swim in some places. Of course, I was not the only one who had this idea. An illustrious group of water enthusiasts had already gathered on the small strip of shore, which was heaped up with sand.

I leaned my bike against a tree and sat down in the shade cast by it.

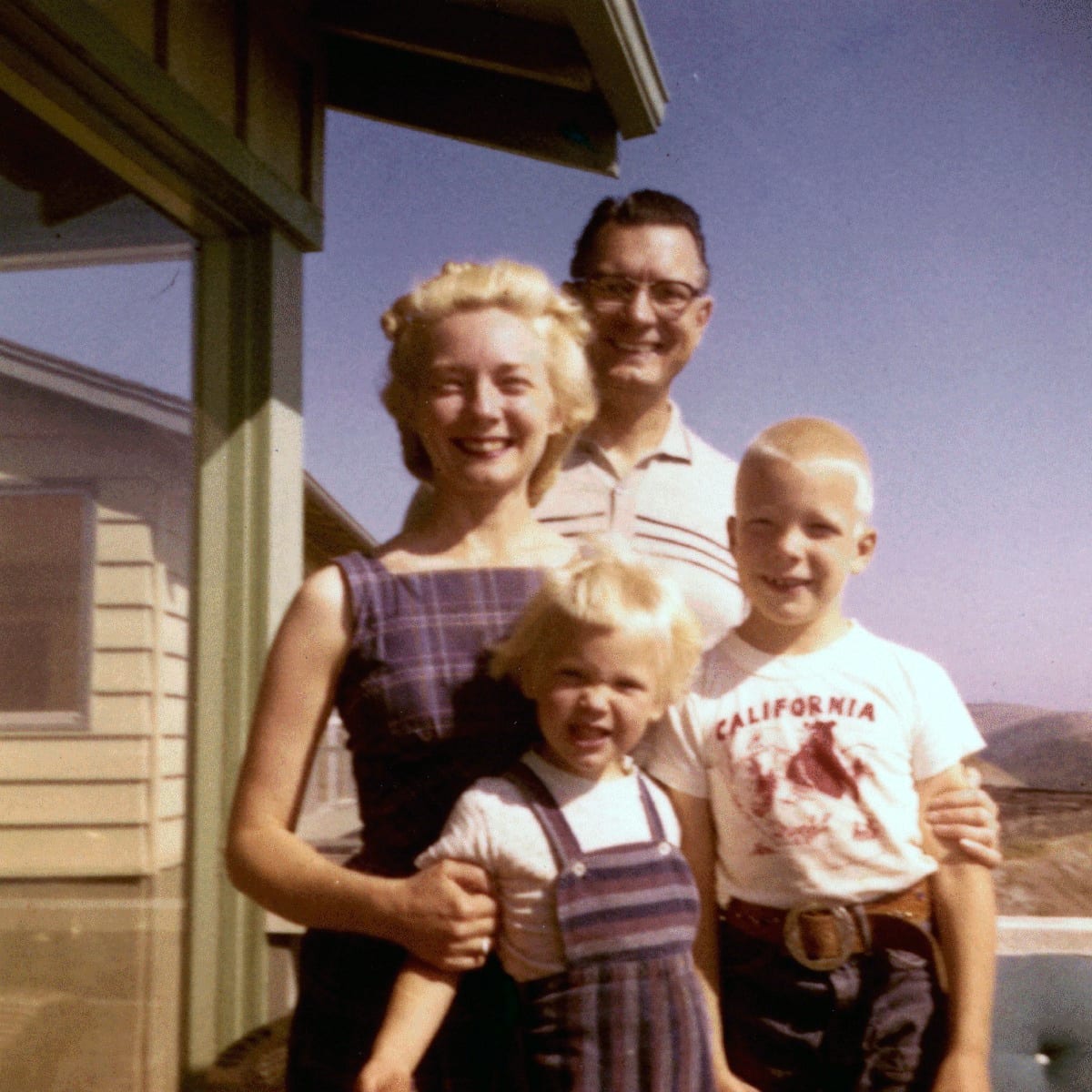

A young family of four who walked along the river attracted my attention. The father, mother and their two daughters were all very smartly dressed. Somehow they reminded me of my own family.

It was very important to my mother that we were always well dressed and looked excellent as a “clan.” She was by no means the only one to do so. Other mothers were as concerned about not leaving their children’s image to chance or arbitrariness.

Image: Seattle Municipal Archives, CC BY 2.0

Meanwhile, the young family had spontaneously decided to interrupt their walk, and take a break in the small bay. The parents spread a small blanket and sat down with their teenage daughter. The younger daughter took off her bright white dress, and in her pink underpants she skipped to the water.

But when she arrived at the water, there was nothing left of her naturalness and light-heartedness.

She was up to her knees in water. And like an elderly person who shied away from water, she hesitantly scooped up water with her hands and carefully doused herself with it. A few times she turned to her family, as if a question was burning under her nails.

Then she plucked up the courage and asked, “Mommy, can I get my hair wet?”

While the question should raise red flags, we may overhear what the question actually implies, and think nothing of it. We may not have the slightest suspicion that our perception may be conditioned (since our own childhood days), and that it is the very conditioning at work why we may not be aware of the implications of the child’s question.

A child asking their mother if they can get their hair wet, suggests they do so because they must think that their hair wasn’t theirs. If they even specifically ask for permission, they do so because they must think they are only inhabiting a body that does not belong to them but was borrowed from the person who gave birth to them.

The child was only 7 or 8 years old, and had already lost control over their own body and mind. This fact is alarming.

Image: Alan Sullivan’s family

We should think that we have a right to exercise our autonomy. In particular, the right to control one’s own body and mind seems to be a basic requirement for a person’s dignity and respect.

Autonomy is the right of self-government. It is a person’s right to determine what happens to them without coercion or external influence.

Per law children are regarded as dependent and in most cases denied the ability to think and act like adults. While our society may afford protection to those individuals who are in a dependent status, in the privacy of a family, there is no control over whether the laws are actually followed.

It is a gray area where parents are free to raise their children as they please.

Accordingly, the development of a child’s autonomy is strongly influenced by the parents or primary caregivers.

While a child shouldn’t have to learn the concept of autonomy in the first place, they are put in a situation that makes it downright necessary for them to learn it.

The opposite of autonomy is slavery. By definition a slave is a person who is deprived of personal freedom, treated as a thing, and as such owned by another.

A child who knows and understands that it is they who have the authority over their own body and mind is less likely to fall victim to any form of abuse – be it sexual, physical, mental or emotional.

It is a bitter truth to swallow that primarily, it is the parents who often put their children in situations where the latter are losing control over their body and mind, and hence are treated as if they were property.

Obviously, it doesn’t happen consciously.

However, the dilemma that the one who violates the child’s autonomy should at the same time be the one who teaches them about it is difficult to solve.

It can be done, though. For it to happen, we need to let our guards down and face the childhood hurt or the primal wound inflicted in our childhood, and – as painful as it may be – relive it and become fully aware of it.

Most of the time we don’t even realize that we carry it. We may even think that we don’t have it. Or ignore, push down, project, run away from it. The wound of unworthiness.

In a cycle of generational wounding our parents have passed it to us. We pass it to our children. Our children pass it to their children’s-children, and so on and so forth. It is a cycle that becomes self-perpetuating until it is deliberately broken.

At the center of it, is a conditional mindset and the ensuing disconnect we all have been subjected to as children.

Continue reading in Can I get my hair wet – part 2

You may also like

What we misunderstand about love

We've been taught that sacrifice equals love, but that's a…

The Mother Wound: Understanding Learned Co-Dependency

Co-dependency often gets trivialized as simply being "too…

Holding the tension of opposing feelings

If only we could stay centered, holding opposing feelings…